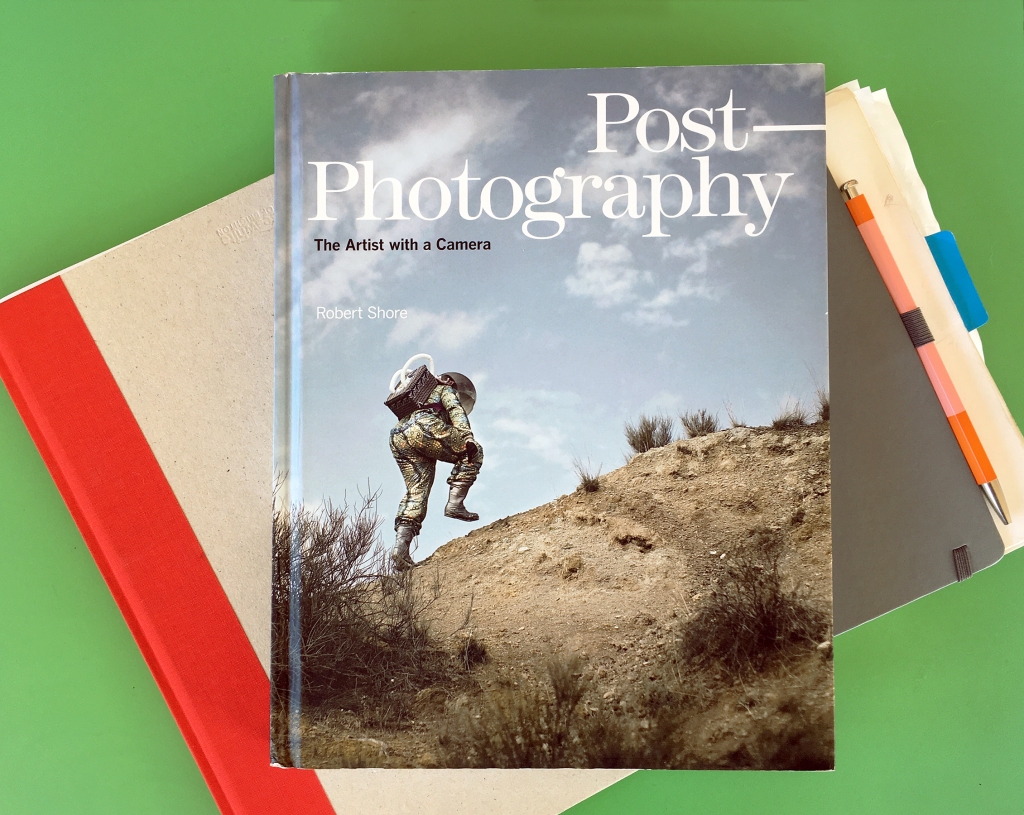

Post-Photography

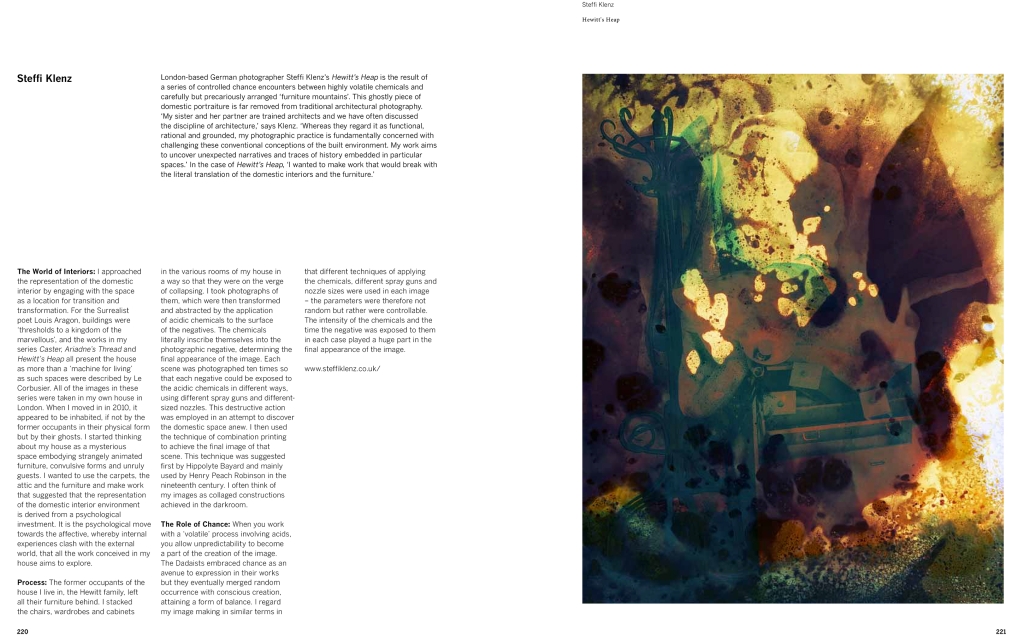

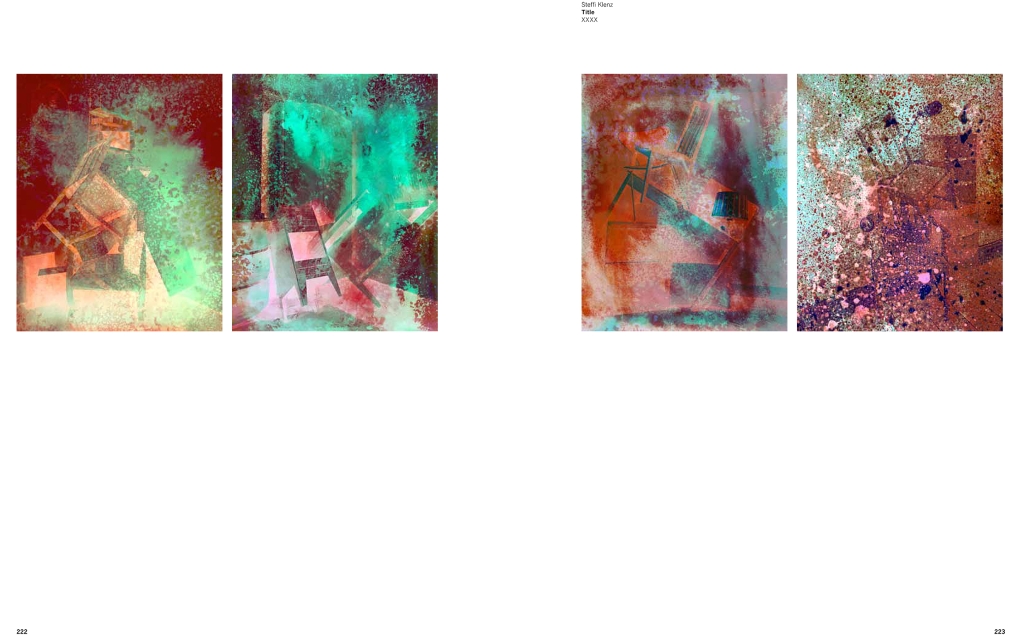

London-based German photographer Steffi Klenz’s Hewitt’s Heap is the result of a series of controlled chance encounters between highly volatile chemicals and carefully but precariously arranged ‘furniture mountains’.This ghostly series of domestic portraiture is far removed from traditional architectural photography.

‘My sister and her partner are trained architects and we have often discussed the discipline of architecture’,‘says Klenz. ‘Whereas they regard it as functional, rational and grounded, my photographic practice is fundamentally concerned with challenging these conventional conceptions of architecture and the built environment. My work aims to uncover unexpected narratives and traces of history embedded in particular spaces.’ In the case of Hewitt’s Heap, ‘I wanted to make work that would break with the literal translation of the domestic interiors and the furniture.’

The World of Interiors:

I approached the representation of the interior domestic by engaging with the space as a location for transition and transformation. For the Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, buildings were ‘thresholds to a kingdom of the marvellous’, and the works in my series’ Caster, Ariadne’s Thread and Hewitt’s Heap all present the house as more than a ‘machine for living’ as such spaces were described by Le Corbusier.

All of the images in these series’ were taken in my own house in London. When I moved in in 2010, it appeared to be inhabited, not by the former occupants in their physical form but by their ghosts. I started thinking about my house as a mysterious space, embodied in strangely animated furniture, convulsive forms and unruly guests. I wanted to use the carpets, the attic and the furniture and make work suggesting that the representation of the domestic interior environment is derived from a psychological investment. All the work conceived in my house aims to explore the psychological move towards the affective, whereby internal experiences clash with the external world.

Process:

The former occupants of the house I live in, the Hewitt family, left all their behind. I stacked the chairs, wardrobes and cabinets in the various rooms of my house in such a way that they were at the verge of collapsing. I took photographs of them, which were then transformed and abstracted by the application of acidic chemicals to the surface of the negatives. The chemicals literally inscribe themselves into the photographic negative, determining the final appearance of the image. Each scene was photographed ten times so that each negative could be exposed to the acidic chemicals in different ways. This destructive action was employed in an attempt to discover the domestic space anew. I then used the technique of combination printing to achieve the final image of each scene. This technique was suggested first by Hippolyte Bayard and mainly used by Henry Peach Robinson in the nineteenth century. I often think of my images as collaged constructions achieved in the darkroom.

The Role of Chance:

When you work with a ‘volatile’ process involving acids, you allow unpredictability to become a part of the creation of the image. The Dadaists embraced chance as an avenue to expression in their works but they eventually merged random occurrence with conscious creation, attaining a form of balance. I regard my image-making in similar terms in that different techniques of applying the chemicals, different spray guns and nozzle-sizes were used in each image - the parameters were therefore not random but rather controllable. The intensity of the chemicals and the time the negative was exposed to them in each case played a huge part in the final appearance of the image.

Robert Shore is a writer, editor and publisher. He is the former creative director for Elephant Magazine and was previously deputy editor at Art Review magazine. As an arts journalist he has contributed to the Sunday Times, the Guardian, and Metro.

(This interview between Robert Shore and Steffi Klenz was firstly published in the book Post-Photography: The Artist with a Camera, published in the UK by Laurence King Publishing in 2014)