He only feels the black and white of it

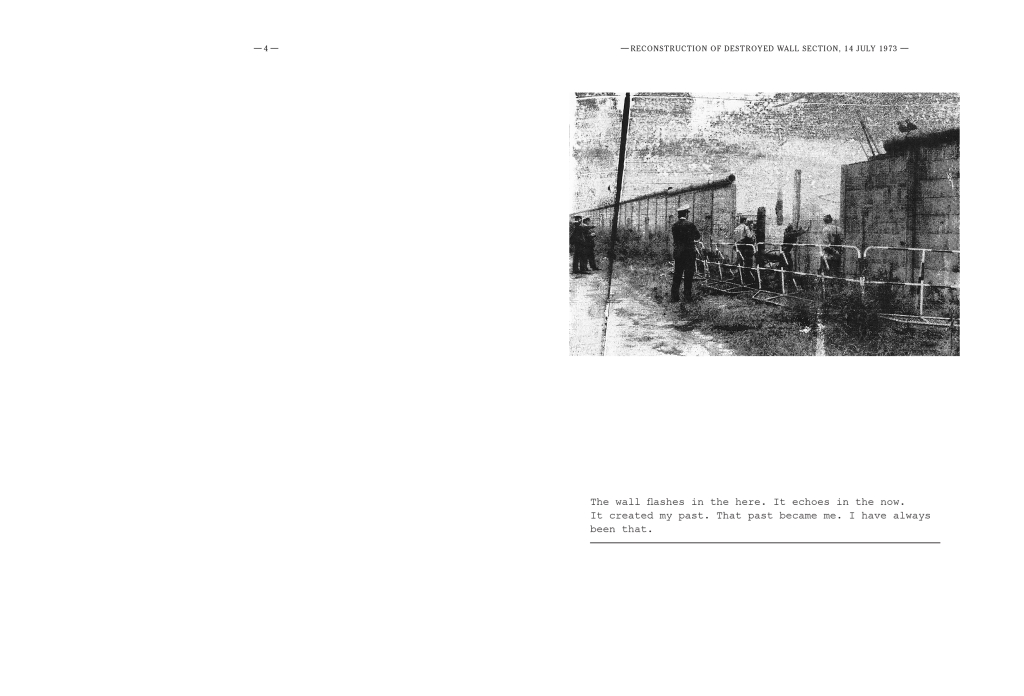

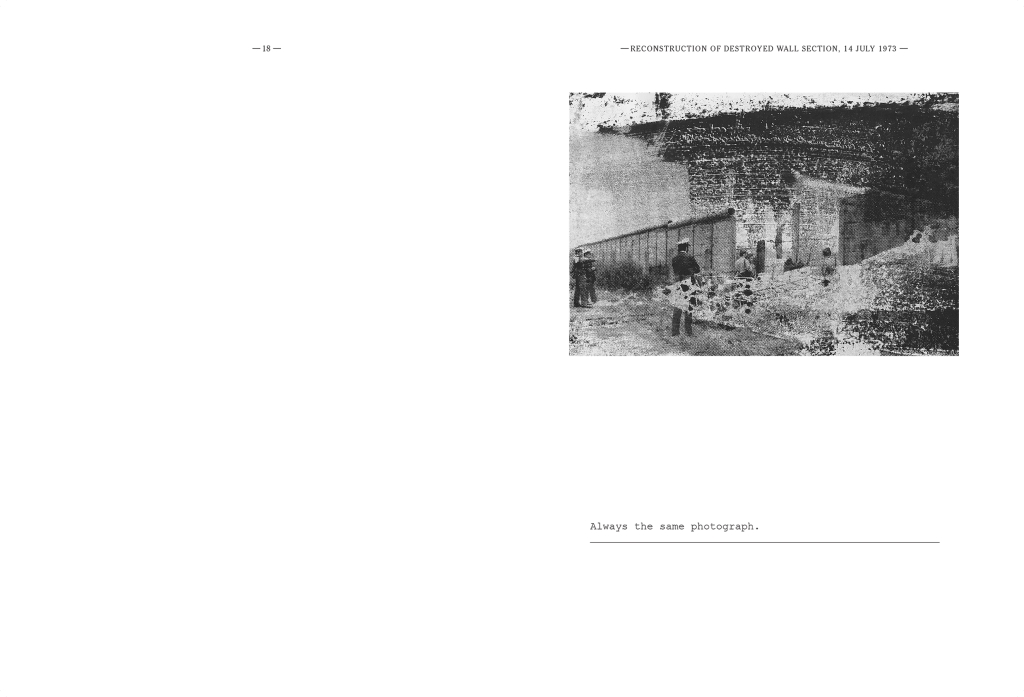

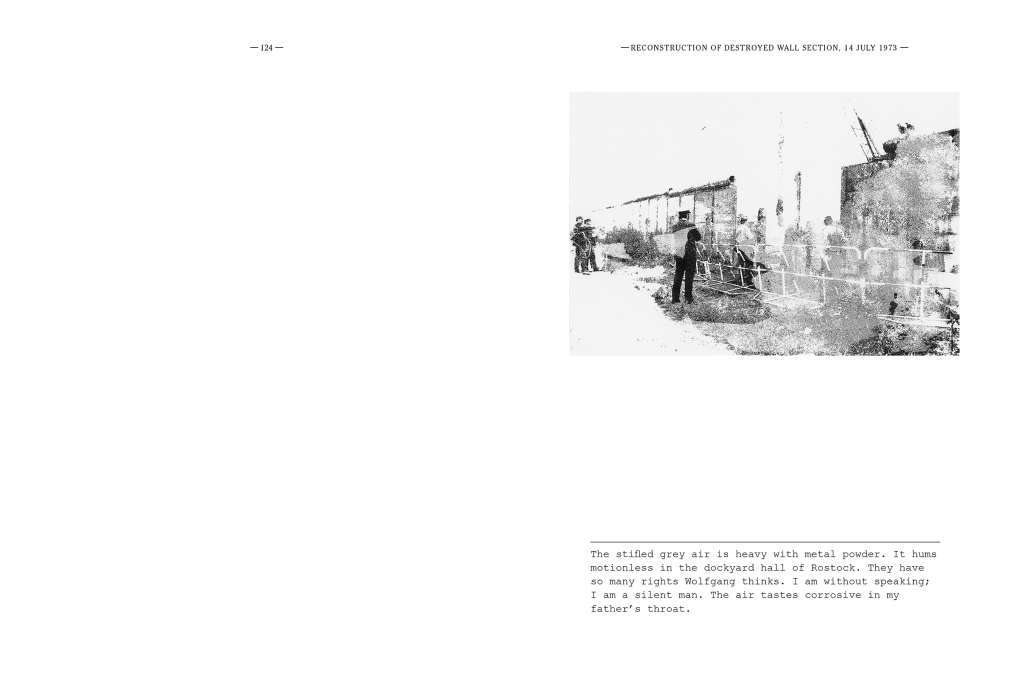

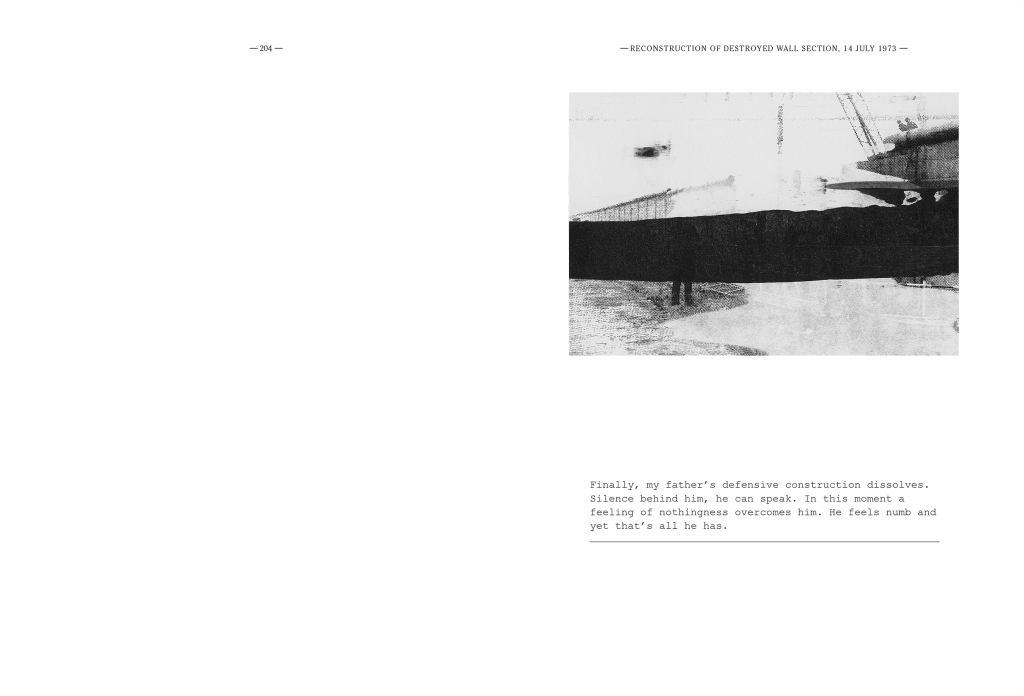

In this book, Steffi Klenz places a sequence of ruptured versions of a 1973 archive press-photograph at the centre: a photograph of a damaged section of the Berlin Wall.

The image pictures East German military guards and border policemen carrying out repair works at the wall. West German had attacked this wall in response to the sound of guns fired at fleeing East Germans.

The image series is combined with an equally fragmented reflective text that evolves around the figure of the artist's father. The text highlights the constraints, pain and loss of identity that he experienced as a young man living in the dictatorial state of East Germany.

Published by MÖREL Books

London, 2016

Edition of 500

Pages 208

17x24 cm

Book review by Ollie Gapper for 1000 Words Magazine

It is as though the pages of Steffi Klenz’s new book, He only feels the black and white of it, Berlin Wall, 14-07-1973 contain a continuum of time all their own – one that exists in tandem with that which is outside of it, but differently.

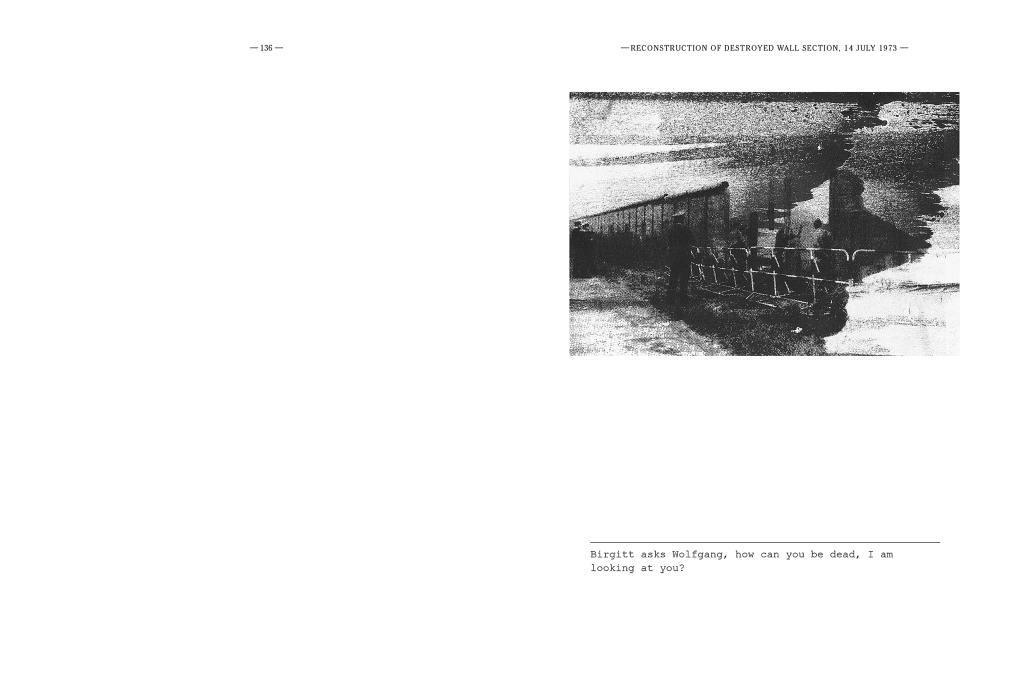

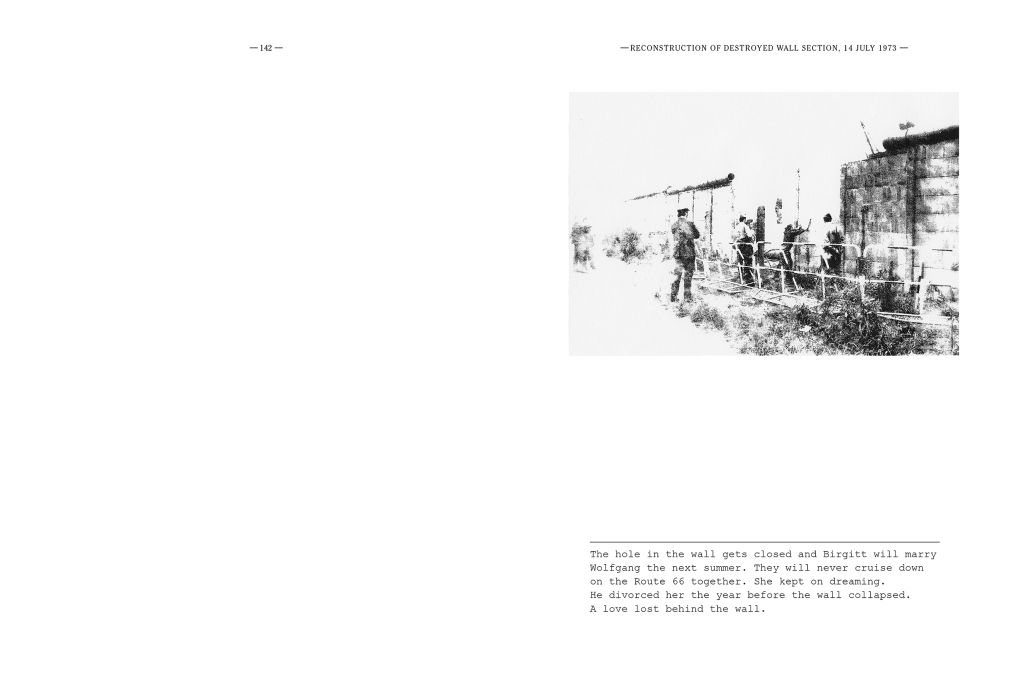

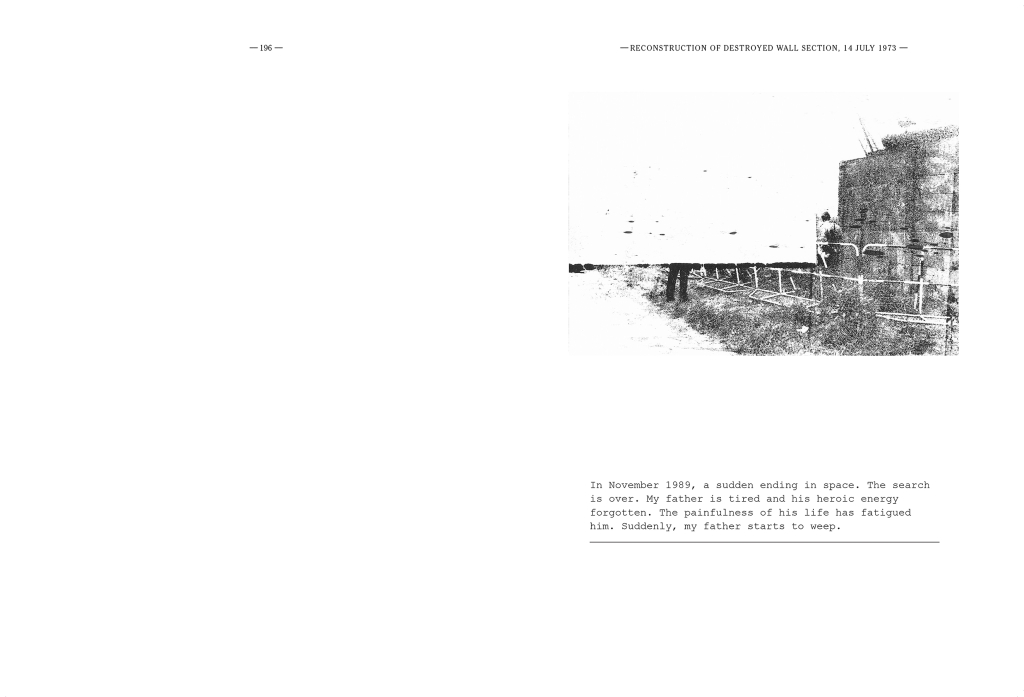

Like cells from a malfunctioning cinema projector, we are presented with a repeating yet different image of the Berlin Wall being reconstructed, one after another. They have been ruptured – some melting, fluid and organic; others shattered, jagged and engineered. The text that underscores them presents recollected fragments from an interconnected cluster of lives from behind the wall. Their power is aggregated; built through the fractured context of their preceding pages, in a narrative structure reminiscent of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s book We. Similarly, the pace for Klenz’s writing snowballs; the speed at which one can read becomes increasingly insufficient to keep up with the growing voracity the written words demand as they compound one another.

A similar maniacal reading manner is evoked from the crudely screen-printed images, their style not so much lackadaisical as furious and energised. When I have discussed the photograph used here with Klenz in the past, it has been one of few things to visibly enrage her. It is this passion that I see pulled and scraped across the prints in the book, not the careful and loving hand of an artisan, but the impassioned hand of a victim. It is as though through this printing she has tried to erase and understand the image – to simultaneously rupture yet piece it together.

Paired with the text, these images present a multiplicitous representation of time in relation to the notion of the pivotal moment. While the cultures of the wider world progress within the texts – with time-anchors such as “Adam Quinn, an American Bagpipes player, is born” along with newspaper headlines and number one songs – the image only shifts in appearance, its reappearance page after page as painfully sedentary as the wall itself. “Time, Wolfgang says, unfolds differently on this side of the wall.”